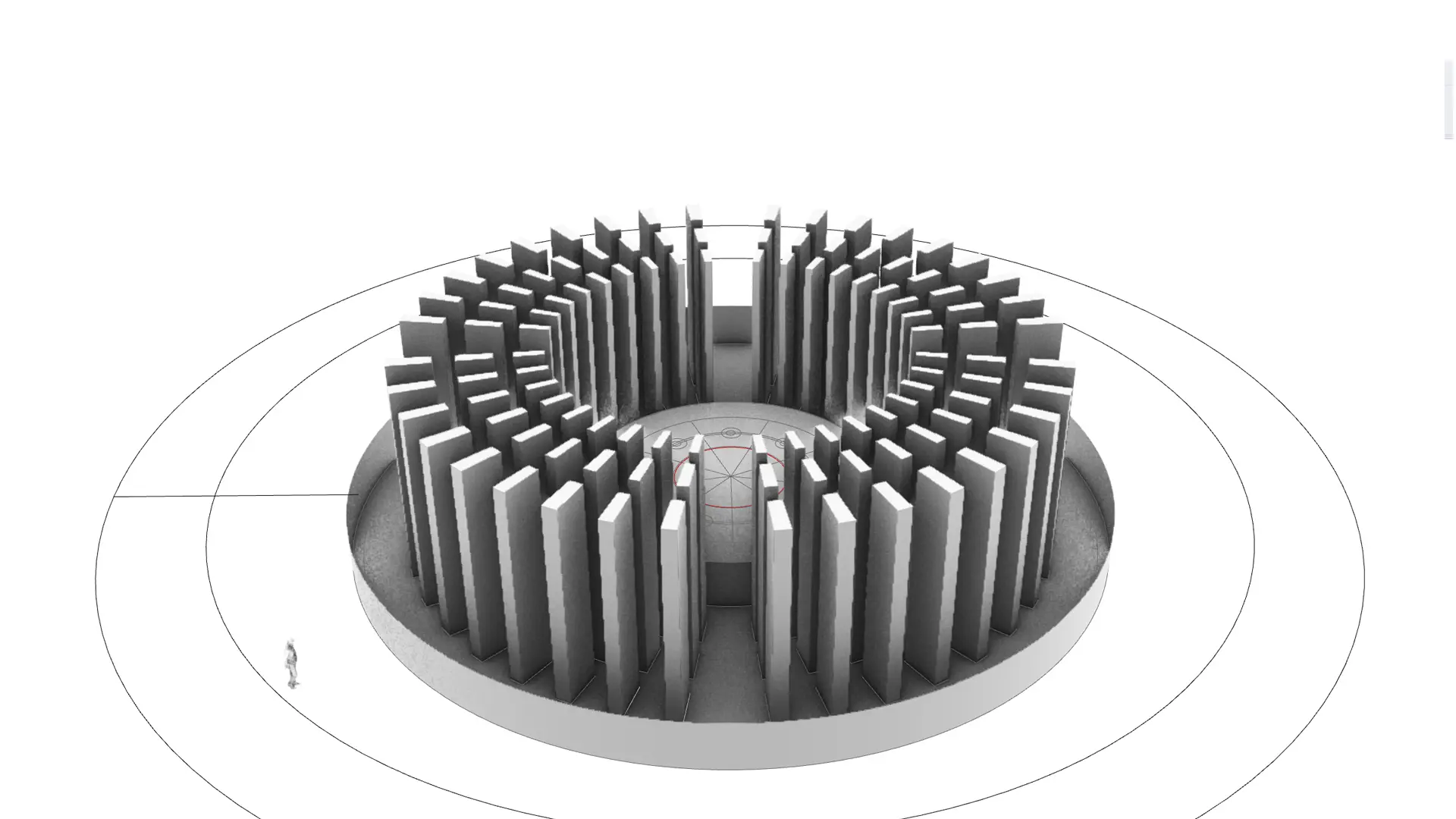

Tower of Silence

Architectural Sculpture

An artistic reflection on enforced disappearance in my birth country

An artistic reflection on enforced disappearance in my birth country

The idea of the Tower of Silence was born in 2006, when I commissioned Olivier Goulet to create a sculpted manifesto for the artist collective I had founded a year earlier, composed of the molded faces of its initial members. The anthropomorphic lines of the concave masks, and the ghost-like illusion created by their convex perspectives, evoked a haunting duality: presence and absence. This tension became the seed of a larger vision, an architectural sculpture capable of embodying both.

The first iteration of the Tower of Silence took shape in Colombia, during a visit to a small artisanal clay brick factory. There, the wooden molds for sun-dried bricks recalled ancient Mesopotamian methods, revealing a pathway to reimagine the brick, not just as a unit of architecture, but as a vessel for identity and remembrance.

Once again, I invited Olivier to collaborate— this time to sculpt a facial mold shaped like a brick. I brought the prototype to South America, where a local metal workshop fabricated concave and convex molds for artisanal reproduction.

The Chitarero were the indigenous inhabitants of Hulago—now known as Pamplona—in the Northern Andes. Members of the Chibchan linguistic family, they revered plural nature deities and practiced ritual cosmology. Oral tradition speaks of Cariongo, a Chitarero warrior who stood against the Spanish conquest. Despite their fierce resistance, the Chitarero were displaced, enslaved, and ultimately extinguished—a people erased from their soil, but not from memory.

Tower of Silence I was constructed at Hotel Cariongo, on the very ground where the Convent of San Francisco once stood. It was there, in the 1550's, that Spanish envoys Pedro de Ursúa and Ortún Velázquez de Velasco, accompanied by Franciscan and Eudist priests, enacted Queen Isabella the Catholic’s mandate: to extract the wealth of the mountains and convert the native population to worship a single god. In doing so, they scarred the identity of my people, dismantled spiritual plurality, and extinguished ancestral cosmic knowledge.

It stands as a sacred, small-scale monument study—an act of transgenerational mourning suspended between acknowledgment and oblivion. A place where the echoes of our vanished native population are never meant to ever fade into silence, exposing the colonial legacy of cultural enforced disappearance as an open wound—unhealed, inherited, and deeply embedded in our national identity.

"Blood Brother, Chitarero

A legacy of longing for the lives in my people.

Let no one dare to think you are forgotten—

For you were free for countless millennia,

Until they hunted you, until they chained you.

Progress swept in and wiped you out.

Blood brother, distant memory—

When you vanished, so did the god of thunder,

The goddess of rain, and even the god of war.

Your All traded by a Gospel."

Libardo Torres

Independent Resaerch at Harvard University

Over the course of two years of independent research in Art, Design, and the Public Domain at Harvard University Graduate School of Design, I had the privilege of working under the mentorship of:

And other internationally recognized faculty whose work bridges theory and practice. I also benefited from unrestricted access to Harvard's and MIT's academic libraries and cutting-edge research facilities. Immersed in a unique tradition of innovative methodologies and critical inquiry, this intellectually rigorous environment allowed me to significantly advance the Tower of Silence.

Art, Design and Public Domain refers to an interdisciplinary field that bridges art, architecture, technology, and design to engage critically with the public space and social realms. It reimagines the city not simply as a built environment, but as a collective urban organism— one capable of shaping civic experience and catalyzing social transformation.

According to the United Nations General Assembly, EID occurs when individuals are arrested, abducted, or otherwise deprived of liberty by state actors or their affiliates, followed by a refusal to acknowledge their fate, effectively placing them outside the protection of the law.

Since 1980, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) has officially documented 61,626 cases across 115 countries, yet only 2% have been clarified. Statistics are “just the tip of the iceberg … many cases are never reported because families are afraid of prosecution or retaliation ... It is estimated that millions of persons have been direct victims of enforced disappearance worldwide".

In Colombia, the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence, and Non-Repetition, created under the 2016 Peace Accord, concluded in its 2022 final report that over 121,768 families were affected by EID between 1985 and 2016— a figure that only partially reflects the true scale of the phenomenon. Today, violence persists, and EID remains a deliberate, systematic tactic of counterinsurgency, oppression, and impunity.

Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance robs not only the victims of life and recognition, but also their families of justice and mourning, opening wounds that never heal.

Particularly interested in merging anthropomorphic forms with experimental clay fabrication in architecture, my research began by analyzing the opportunities and constraints inherent to both artisanal techniques and computational design methodologies.

In collaboration with architect Patricia Lopez Cabeza, we used Rhinoceros to digitally sculpt a self-supporting facial brick designed for architectural deployment. The prototype was 3d printed in PLA: a master mold with a convex face on the front and a concave negative on the back.

At Harvard’s Ceramic Studio, I worked alongside resident artists to develop a six-piece plaster mold capable of reproducing solid, double-sided facial bricks. We further explored slip casting techniques for hollow variants and used ceramic contour 3d printers to produce small-scale porcelain studies.

With the support of architect Sulaiman Alothman, we designed a continuous parametric toolpath in Grasshopper. Starting from the most archaic shape—the circle— we coded five measurable variables: thickness, pressure, speed, weight, and internal architecture. The result was a stratified, abstract, algorithmic human head— a compelling example of how robotic fabrication can inform morphological design.

My clay research culminated in a hybrid sculpture. I sliced the original digital facial brick into 45 flat patterns, laser cut them, then hand-slubbed and hollowed each in terracotta. This final piece reasserted the presence of the artists’ hand guiding digitally driven fabrication processes.

In parallel, I participated in a cross-disciplinary biomimicry research project at Harvard SEAS, in collaboration with Buse Aktas, Shirin Amouei, Maharshi Bhattacharya, and scientists from the Wyss Institute. We studied chromatophores in squid skin to prototype a responsive, bioinspired material with potential applications across micro to macro scales.

This research opened the door to biogenic design, suggesting new possibilities for introducing living organisms into the material ecosystem of a symbolic monument designed to resurrect memory and presence. A turning point, as I began to recontextualize the project and resume the development of the Tower of Silence beyond Harvard’s institutional framework.